The Truth Machine Era is Here

From Iowa in 1988 to the Supreme Court and beyond, the fight over prediction markets was always about one thing: who controls the truth and why the crowd was right all along.

Yesterday on February 17th, CFTC Chairman Mike Selig showcased a historic defense of its right to regulate prediction markets as states came to challenge its authority. You can watch the video here, which he ends with the following assertion of exclusive jurisdiction: “To those who seek to challenge our authority in this space: let me be clear. We will see you in court.”

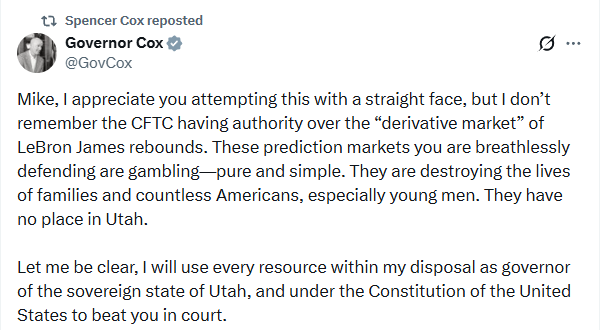

Shortly thereafter, Governor Cox of Utah responded with his own threat, equating prediction markets with gambling and asserting his own exclusive jurisdiction: “Let me be clear, I will use every resource within my disposal as governor of a sovereign state, and under the Constitution of the United States, to beat you in court.”

For those arriving to the drama of Prediction Markets 101, a heartfelt welcome, and a salute to this civil mission. At first glance, it might look as if there is no evident winner in this battle. I am writing this article to fix that impression. More importantly, I am writing this to convey just how important this battle is for sovereign individuals who care about their freedom to engage in lawful economic activity without the overreach of a discretionary state. To understand this, and why there is a clear winner here by both technical and fundamental arguments, we need to understand history: how did we get here in the first place?

A Primary Insight and Its Primal Commercialization

Like most new technologies, prediction markets trace their lineage to academic origins. The Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM) launched in 1988, where the first product was a political futures contract on the 1988 presidential election, Bush vs. Dukakis. To incentivize participation, it was framed as “academic research” with a small cap ($500 per participant) and granted a no-action letter from the CFTC.

It was this exemption, granted under the CFTC's blessing as a research tool rather than a gambling operation, that allowed the model to sit outside regulated exchanges and be exploited as a template for the next three decades.

The results of the studies were striking. The IEM consistently outperformed polls in forecasting election outcomes, lending academic credibility to the core idea that aggregated financial incentives produce better probability estimates than surveys. In other words, the law of large numbers, when financialized, becomes a truth machine.

Based on this insight, the first commercial attempts arrived in the early 2000s with the rise of TradeSports, whose Irish parent company Trade Exchange Network was structured to sidestep U.S. law, offering a preview of the legal geography that would define the industry to this day, and Intrade, its sister platform, which became the most prominent prediction market during the 2004-2012 election cycles. At its peak, there were 50+ million viisitors and $200mm+ in wagers on election-related contracts alone. Most importantly, it correctly called the outcomes of all 50 state-level electoral contests in 2012 except for Florida and Virginia, and hundreds of media mentions cited its accuracies.

It looked like a perfect product market fit.

The CFTC’s Original Sin

Then came the hammer. In 2012, right after the Obama-Romney election, one of Intrade's highest-traffic moments ever, the CFTC filed a civil complaint for offering “commodity options” to U.S. customers without CFTC registration. Intrade immediately blocked U.S. users, and the company swiftly collapsed the following year. Oddly, despite no fraud allegation ever having been raised, the collapse was sealed when a scandal involving missing customer funds emerged. (FTX, anyone? The founder had also mysteriously died climbing Everest the year prior.) The CFTC subsequently reached a settlement with the estate. The collapse left a sober message: operate onshore or die if you touch American money.

The uncomfortable irony is that this financial scandal should have made the CFTC's licensing argument more compelling in retrospect, customer fund segregation, audits, capital requirements, all the infrastructure that would have prevented the money from going missing. It should have resulted in arguments for better regulation, not prohibition. Instead, it created two parallel markets that would haunt the present: one onshore but extremely constrained, one offshore but with little oversight.

It's worth noting there were other onshore efforts too, like HedgeStreet, which later became Nadex (North American Derivatives Exchange), a CFTC-regulated DCM that launched binary options in the mid-2000s offering event contracts on economic data releases and some financial outcomes. But its growth was constrained for two reasons: 1) the CFTC did not permit political contracts, and 2) the binary options space had become a boiler room of epically proportioned frauds.

The most famous poster child of that fraud is not a single company but an entire country: Israel, where investigators estimated $10 billion per year was being scammed from victims worldwide. The platforms were fake brokerages, no trades were actually executed, prices were internally generated, and the house controlled the outcome entirely. (Read up on Banc de Binary for the most famous single company in the scandal.) Israel ultimately banned binary options entirely in 2017, and the CFTC and FBI ran “Operation Binary Options,” resulting in dozens of criminal referrals. This tainted the binary options label and made regulators broadly hostile to anything resembling it.

To summarize all this is to bridge two disparate realities of mental incongruence:

We know political markets are the most interesting and effective, as demonstrated by academic studies and commercial demand that consistently produced better outcomes than polling

But the CFTC had explicitly banned political contracts onshore, creating a parallel offshore market, while simultaneously conflating prediction markets with sports betting in the regulatory imagination

The Dual Ambiguity of “Public Interests” and “States”

So why is the CFTC acting as gatekeeper of the prediction market today? Some argue it traces back to the Commodity Exchange Act, which gives the CFTC jurisdiction over futures and options contracts. However, event contracts, payoffs based on the occurrence of an event, fall into a substantive gray zone, for they are neither futures (linear) nor options (non-linear). It is more likely that because the CFTC historically had authority to ban event contracts “contrary to public interest,” particularly those involving sports and gaming, it became the regulator by enforcement. It found its power through negative covenants, not positive ones, and this is key to understanding why a tripartite conflict persists between the federal level, the state level, and a third more elusive layer: the Wire Act and PASPA.

The Wire Act of 1961 was a Kennedy-era statute drafted specifically to go after the mafia's sports betting operations. However, the core prohibition and resulting ambiguity stemmed from its broad definition of “wire communications,” with no consensus on which activities would qualify. To make the matters worse, unlike the Wire Act's criminal prohibition on conduct, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) focused on a structural prohibition on state action. Specifically, it barred states from authorizing sports gambling schemes (with carve-outs for Nevada and a few others), with the legal theory largely resting on the notion that sports gambling was a federal problem requiring a federal solution. This held from 1992 until the Supreme Court struck it down in Murphy v. NCAA (2018). The outcome rested on the constitutional principle that the federal government cannot compel states to enforce federal law or prohibit states from passing their own laws on a subject. In essence, it removed the federal prohibition on state-sanctioned sports gambling. Sports betting subsequently exploded through state-by-state legalization, but the decision didn't touch non-sports prediction markets, leaving their status once again in the grey. The jurisdictional concurrency would remain until COVID unexpectedly arrives.

The Final Settlement: Political Events

Fast forward to 2020, and we arrive at the next major chapter: Kalshi. Kalshi achieved something no one else had, it became the first CFTC-regulated prediction market exchange in the U.S. for true event contracts, receiving full DCM designation. It was approved for event contracts like “Will the U.S. enter a recession?” or “Will COVID cases exceed XYZ?”, carefully calibrated to engage uncertain events without triggering the gaming prohibition.

Then Kalshi launched the rocket on political event contracts. The CFTC, much as it had in the past, denied these in 2023, ruling they were “contrary to the public interest.” (This should sound familiar by now.) Everyone following the space knows what happened next: Kalshi sued the CFTC in federal court and won. The court held that the CFTC's “gaming prohibition” didn't apply to these contracts and that the agency's public interest determination was arbitrary, a word that will give a minor heart attack to anyone who followed Gary Gensler's decade-long rulemaking around the rejection of Bitcoin ETFs. For what was truly arbitrary, it turned out, was that Polymarket, a U.S.-founded platform with an offshore structure like Intrade, was somehow allowed to operate for foreign users and delivered exactly what the IEM study in 1988 proved: hundreds of millions in volume that was more accurate than polling averages throughout the cycle. By 2024, Polymarket was processing more prediction market volume than any platform in history, with a heavy crypto-native international user base (and presumably many Americans on VPNs).

So where does that leave us today? There is broadly a technical challenge and a fundamental challenge.

The state and federal tension remains unresolved, largely because Murphy v. NCAA left state attorneys general with theoretical authority over state gambling laws. No state has yet moved against a CFTC-regulated exchange, likely because the federal preemption argument under the CEA is strong, but it has never been definitively litigated. This is why Governor Cox's statement is particularly noteworthy.

The deeper and more fundamental unresolved question is: where does “gambling” begin and where does it end? The CFTC lost on congressional control contracts because Kalshi successfully argued two things: 1) “gaming” in the statute means casino-style wagering on games of chance, not financial contracts on uncertain outcomes, like political events, and 2) the CFTC's public interest determination was both substantively arbitrary and procedurally sloppy.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I have long argued that insurance and speculation are essentially opposite sides of the same coin. You cannot have an insurance market without a speculation market on the other side. Most of all, you cannot have a well-functioning market without removing friction from the most efficient price discovery mechanisms: liquidity. We have all played the carnival game where you try to guess the number of skittles in a jar. The law of large numbers always wins when it comes to the intelligence business.

And intelligence, no matter how you dice it, is in the “interest of the public.”

Equally critical is acknowledging that speculation is not inherently gambling. The D.C. Circuit's analysis in the Kalshi case would agree that wagering on games of chance is different from betting on uncertain outcomes. Otherwise, the court would find itself admitting the rather awkward idea that congressional elections are, in fact, a game, a dangerous tightrope to walk in the circus of democracy.

The practical consequence of this cannot be overstated. The CFTC's most intuitive weapon against political prediction markets simply does not work as a matter of law. This is why I believe the floodgates have now opened. No one knows exactly where this goes. But if you set up an events market on it, we'll find out together more accurately than without it. That's the whole idea of this beautiful revolution.

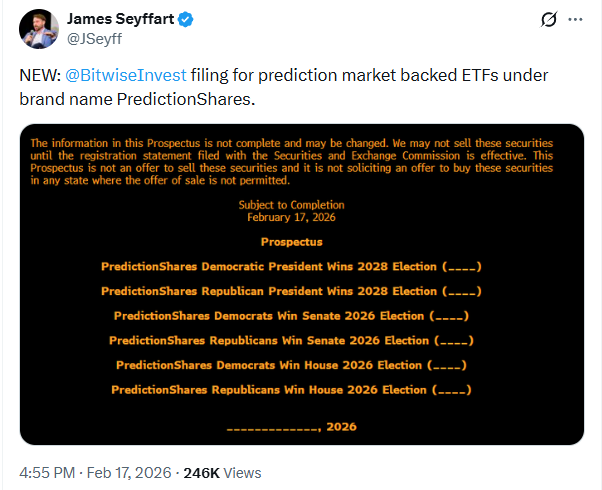

So on the heels of the CFTC announcement the very same day, we saw Bitwise launch a prediction market platform called PredictionShares, positioning it to offer the first ETFs tied to three political events: the presidential election and the congressional majorities of the Senate and the House.

It feels almost poetic that the first market issuers now want to financialize is the very event contract that started it all: the one born in the 1980s over a three-beer lunch between three Iowa professors. What began as a back-of-the-napkin thought experiment has come full circle, returning not as a curiosity, but as the cornerstone of an industry it quietly set in motion.

This is all a welcome development. There are pundits who worry we are hyper-financializing capital markets to the point that it resembles a casino, and while I have some sympathy for those arguments, prediction markets are one of the few places, unlike trading 2x/3x leveraged ETFs or 0DTE options, where a retail investor can genuinely outsmart institutional market makers. The informational edge is no more certain for a market maker than for a retail participant, so long as there is deep, competitive liquidity. That prospect is now far more likely under Mike Selig's courageous stewardship, both in correcting the wrongs of the past and asserting the rights of the future.

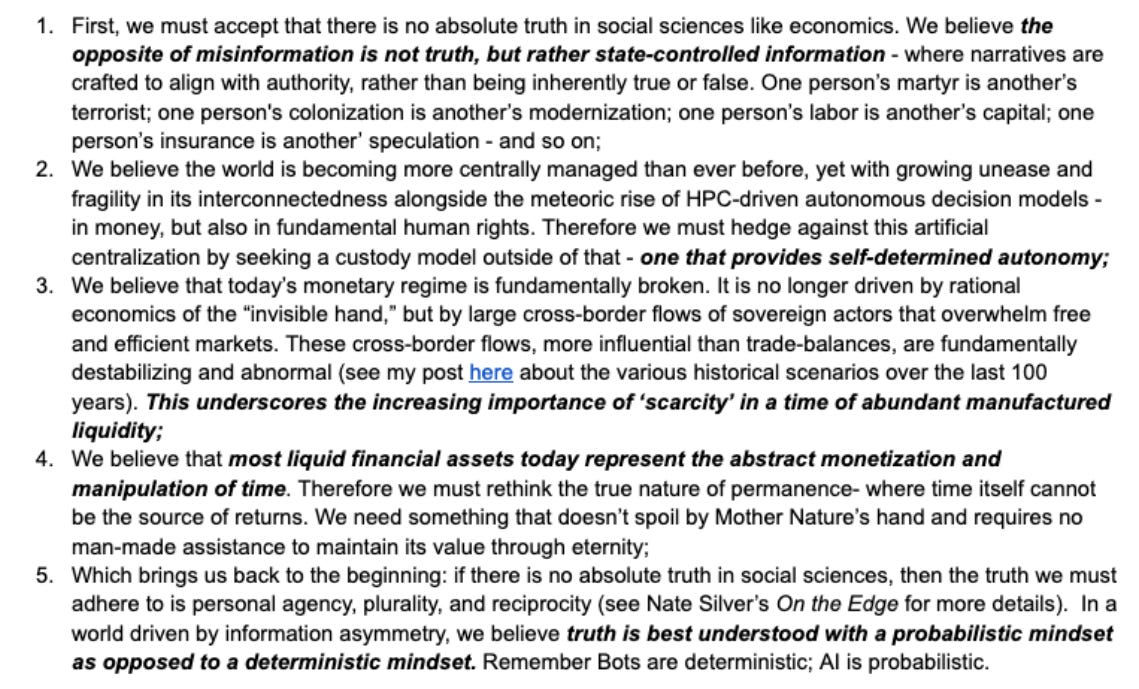

One of the tenets I espouse in my Radical Portfolio Theory and Manifesto is that we must believe in our own agency as truth seekers with a probabilistic mindset. See my five principles below (and here).

I believe prediction markets will become one of the most humanizing arenas the capital markets have ever produced, so long as they are transparently administered with minimal information asymmetry and paired with the right level of financial education. If we expect our kids to understand mortgage math and credit card usury, there is no reason we cannot expect the same from something that, more than almost any new piece of “information technology,” is genuinely optimistic about building human agency.